; Date: Sat Mar 15 2025

Tags: Docker »»»» Docker Development »»»» Self Hosting »»»»

Self-hosting is to host the equivalent of the big-tech Internet services, using open source software, on your own hardware. Docker is typically used for these kind of services since it simplifies administrative chores

Docker revolutionized the way we build and host software services. A Docker container bundles everything required to run an application into a blob, called an image, that is easily deployed into a Docker execution environment. The result is light-weight enough to run on a laptop in the background.

With Docker it's easy to bring up a service and keep it running in the background.

You might need to run a database on your laptop, to easily bring it up and down as needed. You make a directory somewhere, containing a docker-compose.yml, and you're up and running. You type docker compose up any time you want the database running, and docker compose down to shut it down. But what happens as you add more services?

For a laptop you might intermittently need a few services like that, depending on your needs.

When you need more services, and to leave them running full time, it's easy to buy a small computer, leaving it on a shelf, running Docker services. This could be called a "self-hosted homelab".

- Self Hosted means to host services on your own hardware

- Homelab means to have one or more computers in your home (or small office) running services

What kind of services might one self-host?

For most of the "cloud" services offered by Big Tech, there are one or more open source software projects offering similar features.

For example, a software developer like me doesn't need to use GitHub as a source code repository. Gitea has all/most of the same features, and can be easily hosted on a MiniPC on the shelf along with several other services.

I started my self-hosting journey thinking about keeping private Git repositories. I have some projects which should not be visible to the whole world, yet I want to use Git to for keep track of changes etc.

The path of least resistence is to use a cloud Git platform like GitHub or GitLab. With both you pay a fee, such as $7/month, to have private repositories.

But, do the math, and 50 months of $7/month is $350 which is roughly the cost of outfitting a MiniPC with Ubuntu and a few terabytes of storage. Further, that Ubuntu MiniPC could host a bunch of other services some of which might cost $$'s/month. Need simple file storage? Dropbox, Box, Google Drive, and the like will rent you a data storage account at $5/terabyte/month the last time I checked. Or, you can install NextCloud for free and get a whole suite of interesting services.

That Ubuntu MiniPC could quickly pay for itself by avoiding service fees. Plus, you have the peace of mind of knowing that your data is yours.

Here's a few examples to consider:

| Service | Why |

|---|---|

| Nextcloud | For file management, document storage and sharing, calendars |

| Portainer | To better manage the Docker services |

| Plex or Jellyfin | For storing and streaming of video files and other multimedia |

| Immich | Photo storage |

| SterlingPDF | PDF processing |

| Baserow | NoSQL database & tables |

| n8n | Automation |

| Home Assistant | Home Automation |

| Frigate, Viseron | Security cameras |

| Gitea | Github-like user experience of Git hosting |

| Jenkins | Software builds |

| Docker Registry | Local registry for Docker containers |

| MySQL, Postgres, MongoDB | Databases |

| Wordpress or Drupal | Local development test deployment before deploying to a VPS |

There's a whole world of software out there. What will you want to self-host?

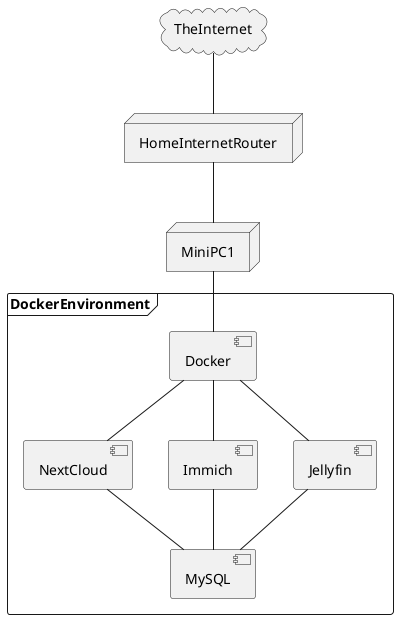

This is roughly what we're talking about. This combination of services might serve a family who is creating, storing, and sharing documents and photos, and storing videos for streaming.

A software engineer like myself might instead focus on NextCloud, Gitea, Jenkins, some databases, a Docker Registry, and the like.

For example, the diagram just above was generated using a PlantUML service I installed in the Docker setup on my laptop. I needed the image, launched the PlantUML service, drew the diagram, and will shut the service down.

Making the host computer visible to the public Internet

We need to briefly talk about a side issue to setting up Docker on a computer. In some cases we want to make the services visible outside our laptop, or outside our home network.

For example, many years I was living in an Eastern Europe capitol for a month while still needing to work using services running on the Intel NUC on my desk at home in California. As a software engineer that work involved using the Gitea and Jenkins services, but I could have just as easily wanted to stream some videos stored on that NUC.

Remotely accessing services in your homelab, meaning in computers running inside your home, can be accomplished by defining domain names pointing to your home internet connection, and by configuring your HomeInternetRouter to forward traffic to the MiniPC.

For some discussion, see: Use DynamicDNS to give your homelab services on your home internet connection a domain name

Installing Docker

Docker is fairly easy to install. For instructions to do so on every operating system:

See Installing Docker Engine or Desktop on Ubuntu, macOS or Windows

A directory hierarchy for managing multiple Docker containers

The issue is how to manage an ever-growing set of services to self-host.

What I do is to set aside one directory to be the parent of several directories containing files for managing the containers.

The parent directory might be /opt, /home/docker, /home/USER/docker, or even /docker. The idea is to put all Docker resources in one place for ease of management.

In /home/docker the intention is to have one directory per project. A project might require multiple containers.

| Service | Directory |

|---|---|

| Nginx | /home/docker/nginx |

| Gitea | /home/docker/gitea |

| Jenkins | /home/docker/jenkins |

| Nextcloud | /home/docker/nextcloud |

| Jellyfin | /home/docker/jellyfin |

| Registry | /home/docker/registry |

| Portainer | /home/docker/portainer |

| MySQL | /home/docker/mysql |

That's an example of what one might do, and is more or less what actually exists on my computer.

Within each directory we have these things to manage:

- Scripts related to building and upgrading the container(s)

- Configuration files used inside the container(s)

- Data directories used by the container(s)

As an example consider:

david@nuc2:~$ ls /home/docker/gitea

app.ini data docker-compose.yml gitea-data README.md

Therefore we can define a general architecture:

/home/docker/SERVICE-NAMEcontains everything related to the service- Use

docker-compose.yml(orcompose.yml) to document the configuration - For any configuration files, store them outside the container and use Docker to mount the config file inside the container

- For any data directory, do the same

- Use a

README.mdto record any notes or instructions - Use shell scripts or build automation tools to record any shell commands that are required

Starting and stopping services

Portainer is an advanced system for managing multiple Docker or Kubernetes instances. There is a free community edition, that's very advanced, and an even more advanced enterprise edition.

With its GUI you can start/stop services, inspect their status, view the logs, connect to a shell inside the container, and more.

But, while it's convenient, one can get accustomed to command-line administration:

# Check the current status

$ docker ps

# Launch services using Compose

$ docker compose up -d

# Bring down services launched using Compose

$ docker compose down

# Look at logs from services launched using Compose

$ docker compose logs -f

These are frequently used commands, and there are MANY additional commands. The last three must be executed in the directory containing the compose.yml used for launching the services.

Upgrading or downgrading Docker services

The authors of Docker images fix bugs and add features. That means you will want to update to a newer Docker image. Or, maybe, you need to select a specific version of the image to avoid using a later version.

One way to approach this is, in a Compose file, to specify the desired (or newer) version of the image. Technically, Docker images do not have a version number, but they have a tag. Practically speaking, the tag is typically a version number.

To make a concrete example, consider

https://hub.docker.com/_/node

This image provides everything required to run Node.js applications. Browse the tags tab and you'll see the primary feature of the tag strings is the Node.js release number. For example, 23.9.0-slim, 23.9.0-alpine3.21, 23.9.0-alpine, 23.9.0, 23.9-slim, 23.9, 23-slim, and 23, are different ways to slice-and-dice a specific release number as well as different Linux releases.

Each image author follows their own policy for determining tag strings.

The scenarios include:

- Upgrade to a newer release -- To use new features or fix bugs

- Downgrade to an older release -- If a new version fails, you might revert to an older version

- Maintain use of a specific release -- If you are happy with release N and are worried release N+1 will break something

Sticking with a specific release would mean, for example, the node:22.14.0 image (the current release as of this writing). Your Compose file might be referencing the node:22 release, and when you decide to pin your Node.js version on 22.14.0 you might have to completely spell out the version number.

Likewise, upgrading to a newer release, or older release, means to change the tag name reference. Going to an older release might mean the node:20.19.0 image, and to a newer release might mean the node:23.9.0 image.

After you've edited the Compose file to select a different tag, or version number, for your containers, run these commands:

# Bring down the services

$ docker compose down

# Pull down the desired container version

$ docker compose pull

# Restart the Compose file

$ docker compose up -d

For some software, upgrading or downgrading the software might mean transitioning a database or configuration files if there were incompatible changes between the currently used release and the one you switch to.

Summary

Docker is a powerful ecosystem with a huge variety of prepackaged applications available for your use.

We have seen that it is relatively easy to install and use.

You can use it on your laptop, bringing up services as needed. Or, you can buy a small MiniPC letting you install long-running services. Or, you might run a business where it makes sense to install a few local machines on which to run Docker services rather than pay for commercial cloud services.

Self-hosted software means you have control over your data, and you know the Big Tech company isn't misusing your data for their ends.