; Date: Wed Aug 19 2020

Tags: License Plate Recognition »»»» Tracking »»»»

A new initiative, TALON - the Total Analytics Law Officers Network, aims to build a nationwide (USA) license plate tracking system for law enforcement. The company behind this effort, Flock Safety, talks glowingly of the benefit of more efficiently capturing suspects. But what about instances of false identity?

The introductory website about TALON - the Total Analytics Law Officers Network tells a very moving story of how the Flock Safety founders helped their local police to solve a series of crimes. Garrett Langley, a Flock Safety co-founder, lives in a neighborhood where there had been a series of break-ins. When he called the police for advice, the Police Captain said to look into a "license plate reader". Langley found that existing models were in the $25,000 range. Instead of buying one of those, Langley teamed up with "Matt" (a software developer) to develop a prototype unit, and in 60 days they were able to give evidence to the police which led to an arrest.

That experience led to launching Flock Safety, with the goal of reducing non-violent property crime. The TALON website says "Flock Safety has thousands of license plate readers across 700 cities in the US", and that police departments are using the system to solve dozens of crimes a day.

An example cited is an incident in which a Lamar County GA Sheriff’s Deputy had a late night call about a domestic disturbance. Upon arriving at the location, the Deputy was immediately fired upon by several shotgun blasts, and fortunately the Deputy survived, but the culprit sped away in a white pickup truck. In olden times, just a few years ago, that might have been the end of the story with little opportunity to catch the culprit. But, this person drove past nearly 100 license plate readers, and was ultimately arrested in Pell City Alabama, over 170 miles away.

TALON - the Total Analytics Law Officers Network

In a

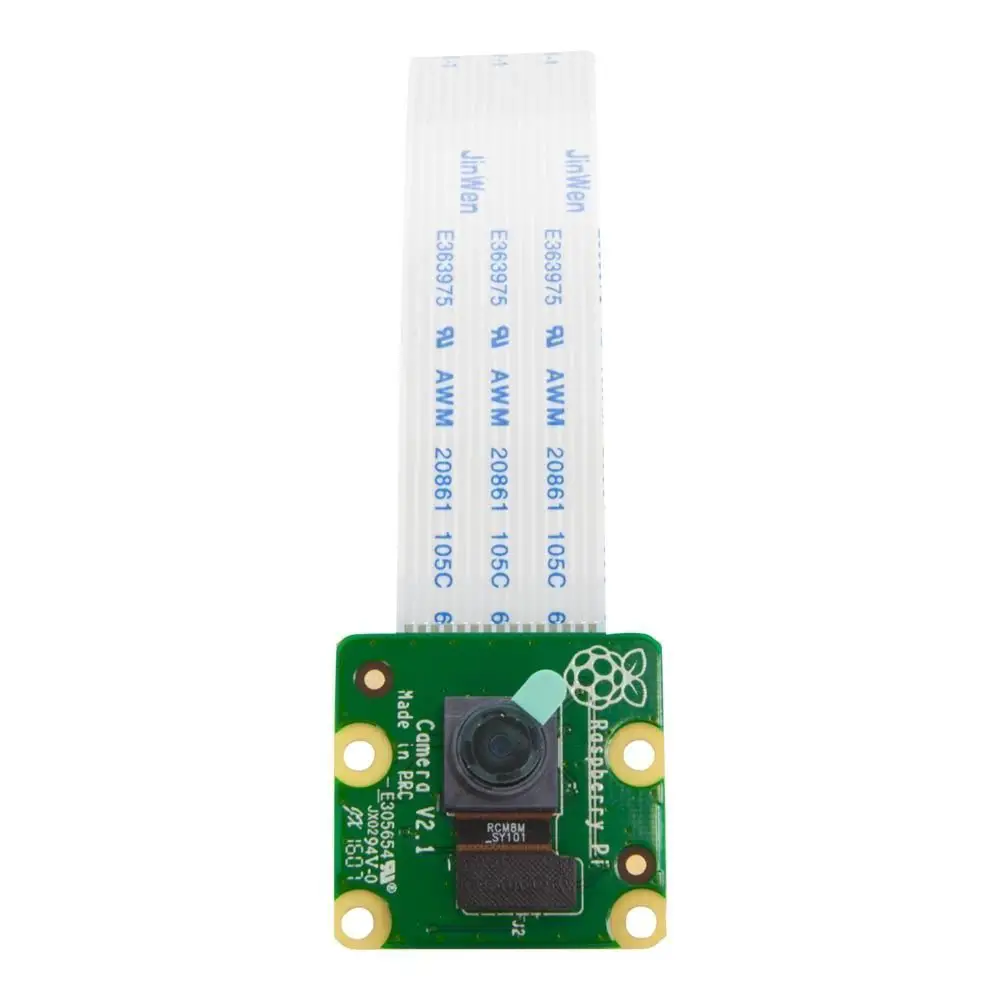

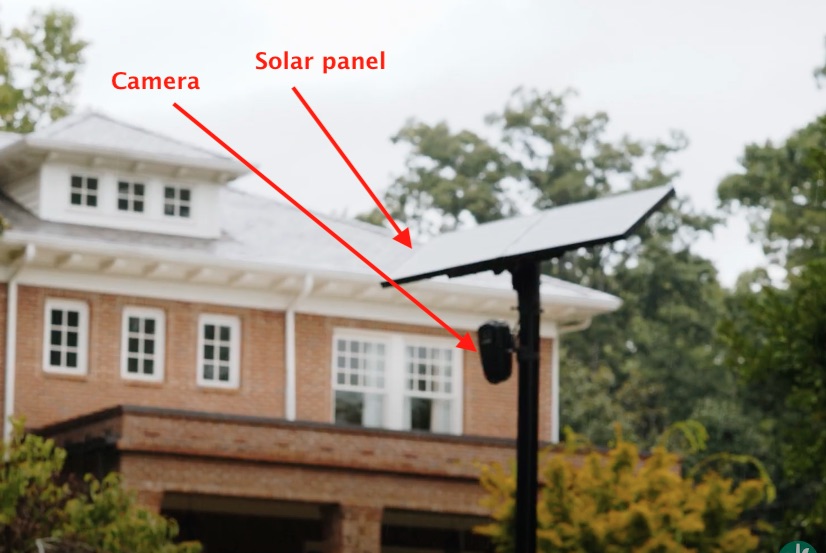

Flock Safety Overview it is described as a camera, and cell-phone-system communications equipment, that is solar powered with a local battery-based energy storage system. The whole unit easily mounts on a pole, and constantly records license plate information sending it to a centralized collection system on the Internet.

This should give an idea of what the system is like when installed. It is installed on a dedicated pole, rather than attached to a city light pole or a utility pole. The black box has an infrared light (that's the circle of LED's here) and a camera.

Within the box is a computer plus equipment for data communications over the cell-phone system. The current box would be using 3G or 4G data communications, but is precisely the sort of "Smart City" device envisioned for the 5G system.

The cost is described as $2,000 per camera per year. That includes all service and support, software upgrades, etc. The speaker goes on to say that for a 50 home neighborhood, that roughs out to $40 per home per year. And the video seems pitched more to homeowners groups rather than to Police departments.

Watch the video carefully, and then ask yourself what sort of neighborhood is expected to adopt this system? The image above gives a clue, since the house shown here is not a poor persons house.

For example:

Immediately after saying "$40 per home per year" the video pans over this neighborhood scene. It's a fairly typical cul-de-sac situation and looks to have one entrance onto a busy street. Therefore, a single camera pointing at that entrance would collect data about all travel in and out of that neighborhood. Therefore, if a crime did occur in this otherwise sleepy corner of the city, there would be a complete track of all vehicles.

It's easy to imagine that with such data the police department could easily track down which vehicle contained the culprits.

TALON and the Total Information Awareness System

The name TALON - the Total Analytics Law Officers Network immediately raises in my mind a US Defense Department project from 2000-2001, the Total Information Awareness System.

Back in 2002, I happened to have collected a summary of that project which I have published here:

DARPA's Information Awareness Office, The Total Information Awareness System; Or, Big Brother in-carnate

In that time frame the Internet and the computer industry was much less developed than today. It was the earliest period of what was then called Data Mining, which later became called Big Data, and is now called Data Science. The idea behind the Total Information Awareness System was to apply those tools to government intelligence work, so that the Federal Government could more readily intercept potential terrorist attacks.

But to do this required capturing all kinds of data from the innocent activities of innocent people. For example, they wanted access to all credit card transactions in order to detect the few transactions containing clues of a budding terrorist attack.

To discuss that project any further would distract us from examining TALON, but it is worthy of mention.

Looking for evidence with TALON

The system, TALON - the Total Analytics Law Officers Network, seems to be more geared to use by police departments. We are told:

TALON is a local and national network of ALPRs for law enforcement who want to verify a specific license plate’s location. Get access to local and national vehicle reads each month so you can gather the evidence you need to close more cases.

And that:

We built TALON with law enforcement in mind, and with a new ethical framework for how to leverage the footage.

But... the video linked above shows this scene of an "authorized" person looking up video in the TALON system. I don't know about you, but this does not look to me like a police officer.

The video describes a system where authorized users -- presumably the authorized users can include not just police officers -- make queries into the system to filter all the data it collects. The filtering is not just on license plates, or license number fragments, but also vehicle type, vehicle color, location, time of day, etc.

Implementing such a system requires data analysis, artificial intelligence, machine learning, computer vision algorithms, etc. It's not just enough to capture images. The software system must be able to recognize important elements from the images, like the attributes just named. Recognizing the vehicle make/model/type/color, requires sophisticated analysis and pattern recognition. Finding the license plate number from video of a moving car also requires sophisticated analysis.

But this leaves me wondering just who is allowed access to the system.

Ethical collection and use of automated license plate number data

Flock Safety proclaims to have designed

ethics into their Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) network. This is supposed to make us feel comfortable that data collected about us is being treated ethically.

The company claims these two ethical principles in their founding:

- it's possible to leverage technology to eliminate crime and

- it's possible to build technology within an ethical framework that protects privacy.

While discussing ethics, Flock Safety brings up a partnership with

Axon, a provider of Tasers, Body Cameras, and computer gear for police departments. One thing this partnership did was connect Flock Safety with an independent review board, and a system of fifteen principles:

- Law enforcement agencies should not acquire or use ALPRs without going through an open, transparent, democratic process, with adequate opportunity for genuinely representative public analysis, input, and objection. To the extent jurisdictions permit ALPR use, they should adopt regulations that govern such use. (This is what we said about face recognition, and it is true as well for ALPRs.)

- Agencies should not deploy ALPRs without a clear use policy. That policy should be made public and should, at a minimum, address the concerns raised in this report.

- Vendors, including Axon, should design ALPRs to facilitate transparency about their use, including by incorporating easy ways for agencies to share aggregate and de-identified data. Each agency then should share this data with the community it serves.

- Vendors, including Axon, should design their ALPRs so that agencies can adjust the list of vehicles to which an ALPR will alert law enforcement officers, so that the list includes only those offenses or reasons most of concern to that agency and its community. Although communities must decide the contours of their own alert lists, as a general matter we believe that these lists should not be used to enforce civil infractions, offenses enforceable by citations, or outstanding warrants arising from a failure to pay fines and fees.

- Vendors, including Axon, must provide the option to turn off immigration-related alerts from the National Crime Information Center so that jurisdictions that choose not to participate in federal immigration enforcement can do so.

- ALPRs must be designed and operated in ways that ensure alert lists are checked routinely for errors and kept up to date.

- An ALPR alert, on its own, should not constitute sufficient grounds to stop a vehicle. Officers must make visual confirmation independently that the license plate matches the hot-listed plate. If the offense at issue is associated with the registered owner of the vehicle (as opposed to the vehicle itself), the officer also should ascertain whether the driver is consistent with the description of the registered owner.

- Axon should work with partner agencies to determine the shortest possible retention period for ALPR data that will serve law enforcement needs sufficiently (as explained below), and set that period as the default retention setting on its ALPRs.

- ALPR design should create audit trails both of real-time ALPR alerts and agency accessing of historical ALPR data. Law and agency policy should require regular auditing of ALPR usage.

- Stored ALPR data must be encrypted and secured against outside access and breach.

- ALPR vendors should not retain the right to access or share ALPR data, and law enforcement’s ALPR data should never be shared for use by for-profit third parties.

- ALPRs should be designed such that if agencies share data with other law enforcement agencies, they do so transparently and in a way that is governed by formal and lawful data-sharing agreements.

- Vendors, including Axon, should never profit from fines and fees obtained through law enforcement use of ALPRs.

- Vendors, including Axon, should provide adequate training materials for agencies and officers using its ALPRs, including about default settings and why they are set the way they are.

- It is imperative that data-gathering and impartial study be conducted of ALPR usage, so that communities and the country are aware of how ALPRs are being used, of what is required to make that usage effective, of any harms arising from ALPR usage, including whether ALPRs are exacerbating disparities, and of ways to eliminate or mitigate those harms.

While all this sounds good - it also feels like a flurry of words meant to convey goodwill, but is there any depth to it?

Known misuse of data from automated license plate readers

Documents Reveal ICE Using Driver Location Data From Local Police for Deportations -- This is a March 2019 report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) detailing records obtained from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement about:

ICE’s sweeping use of a vast automated license plate reader (ALPR) database run by a company called Vigilant Solutions. Over 9,000 ICE officers have gained access to the Vigilant system under a $6.1 million contract that the public first learned of last year. ICE has access to over 5 billion data points of location information collected by private businesses, like insurance companies and parking lots, and can gain access to an additional 1.5 billion records collected by law enforcement agencies.

This amounts to a nationwide surveillance network operated by a private corporation but accessed by police departments, and ICE, nationwide. It isn't Flock Safety, in this case, but another company.

In a July 2020 incident in Aurora GA,

Cops Terrorize Black Family but Blame License Plate Reader for Misidentifying 'Stolen' Vehicle, data from an automated license plate reader misidentified a minivan as a stolen motorcycle. Based on that data, police officers stopped the family in that minivan, holding them at gunpoint, forcing them to the ground, and handcuffing some of them. Their minivan had not been stolen, and the driver of the van was the registered owner of the vehicle.

According to a statement from the Aurora Police Department, as soon as the mistake was discovered, they ended the confrontation and apologized. But, couldn't that situation have escalated into violence and a dead family?

Summary

This service is spun as a useful thing. We're led to believe that this automated computerized surveillance technology will lead to safer neighborhoods and criminals that are more efficiently brought to justice.

But - what about the neighborhoods that cannot afford $2000 per camera per year?

But - what about the potential misuse of the data? It isn't clear just who has access to the collected data, and whether the system truly protects our privacy.

There is plenty of room for mistaken identities. Artificial Intelligence systems are all the rage nowadays, but they are not without limitations. AI machine learning systems rely on statistical models -- in other words, computerized guesswork. Using those statistical models, the software will determine the make/model of the car, but what if the statistical model guesses wrongly? And then by having guessed wrongly, the wrong person gets pulled over, and in the confrontation is killed by police?