; Date: Tue Aug 21 2018

Tags: Facebook »»»» Social Media Warfare »»»» Hate Speech »»»»

What steers a peaceful young man to commit violence? We say Muslims can be radicalized by information they find online, causing them to commit violence like terrorist missions. What if that person is instead an American, or German, practicing Christianity, who suddenly commits violence? A recent study of anti-refugee attacks in Germany suggest a strong correlation with Facebook usage, especially if one is flocking to hard-line right-wing groups or postings.

The NY Times reports today on a study looking to correlate Facebook usage with anti-Refugee sentiment, and anti-Refugee attacks, in Germany. Karsten Müller and Carlo Schwarz, researchers at the University of Warwick, scrutinized every anti-refugee attack in Germany, 3,335 in all, over a two-year span. They ran statistical analyses over many possible variables before settling on Facebook usage.

A problem with the NY Times article emerges at this point. All through the article it's claimed the research correlated Facebook Usage (as in -- general usage of Facebook) with anti-Refugee attacks. Instead the researchers focused on folks associated the Facebook presence of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

AfD is a far-right political party in Germany who is routinely posting content that fans the flames of anti-Refugee hatred.

The research found a strong correlation between localities that have folks who read AfD materials, and acts of violence. Such places have more acts of anti-refugee violence than do areas where nobody reads AfD materials.

The NY Times reporters traveled to a few places in Germany to look at the effects first-hand.

They found a young firefighter trainee who'd become engrossed in anti-refugee materials on Facebook that one day he decided to commit arson in a refugee group home in his town. And they found other folks who are seemingly regular every day people, but are spending lots of time sharing this sort of material on Facebook.

The process is a kind of radicalization. The more one see's this material the more one believes it is true, and then it is easy to believe action is required.

Research Results

The paper chose two clusters of people, those engaged with Nutella (the popular food brand), and those engaged with Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Tracking folks engaged with Nutella serves as a kind of control factor, because its content is so benign and because it is so popular, and also to gauge which localities with more Facebook users.

To gather the data, researchers used the Facebook Graph API to track all postings on both groups, and the comments. The researchers did not receive personal identity information but some kind of unique code for each person.

From the paper:

Consistent with the hypothesis that hate speech is transmitted through social networks, the size of the effect on hate crime is higher in regions where AfD users show higher engagement on Facebook via likes and comments.

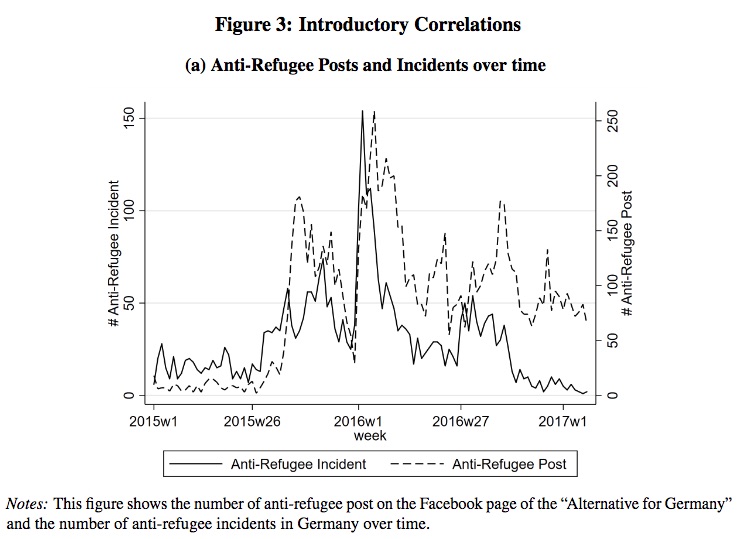

First, we plot the total number of posts on refugees on the AfD’s Facebook page against the number of anti-refugee incidents in Figure 3a. Weeks with more anti-refugee posts also tend to have more anti-refugee incidents.

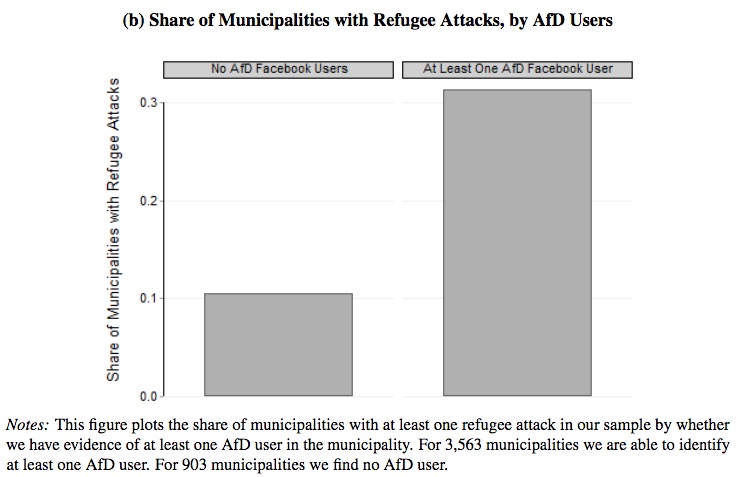

The next relevant question is whether refugee attacks are concentrated in areas with more right-wing social media users. Figure 3b shows the share of municipalities with at least a single refugee attack, depending on whether we can identify at least one AfD user. The share of municipalities with attacks is around 10% for municipalities without and around one third for municipalities with AfD users. Out of the total 3,335 attacks on refugees in our sample, 3,171 occurred in municipalities with AfD users.

Person-level view of radicalization

Getting back to the NY Times article, it focused on one city, Altena. In that city a young firefighter trainee, Dirk Denkhaus, had set fire to a group house occupied by a group of refugees. He broke into the attic, doused it with gasoline, and set fire to the gasoline. Nobody was injured, but the attack shocked folks especially as Denkhaus had been seen to be a nice guy.

Police found through studying his online behaviors that he, and a group of buddies, had begun sharing anti-refugee postings with each other. The vitriol ratcheted up and up until one day Denkhaus said they have to do something. That same day, he and a friend set fire to that refugee group house.

The NY Times article doesn't use this phrase -- but that sounds like a process of radicalization. Again, when a Muslim spends time in certain discussion forums or other online areas and then commits an act of violence, we say that person was Radicalized by online content. In this case, a nice German man went through a similar process, then committed violence, so should we not use the same phrase? He was radicalized by the anti-refugee postings he found.

There is a wide range of material online, if you search it out, espousing all kinds of hatred for this group or that group. It seems there are many who see their mission in life as spreading anger or hatred or fear. Hunt around Facebook and you can find pages espousing all kinds of things.

In Altena, the Mayor had asked for an extra allotment of refugees. In 2014/2015 everyone was all concerned over the plight of these people escaping the horrid conditions in their home areas. There were so many refugees in Altena the "refugee integration center" couldn't keep up, despite the flood of folks eager to help with language lessons and the like. Anette Wesemann, the organizer of the refugee integration center, said she started a Facebook page to help organize the volunteers, but then that page filled with "anti-refugee vitriol of a sort she hadn’t encountered offline."

Some of the posts appeared to come from non-Altena people.

At trial Denkhaus was portrayed as a nice young man, until he got to Facebook. Specifically:

Mr. Denkhaus had little opportunity to encounter anti-refugee hatred in the real Altena, where overwhelmingly tolerant social norms prevailed. But within his Facebook echo chamber, he could drift unchecked toward extremism.

Source:

nytimes.com 2018/08/21 facebook-refugee-attacks-germany

Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime

Source:

papers.ssrn.com

80 Pages Posted: 7 Dec 2017 Last revised: 24 May 2018 Karsten Müller University of Warwick - Warwick Business School

Carlo Schwarz University of Warwick

Date Written: May 21, 2018

Abstract: This paper investigates the link between social media and hate crime using Facebook data. We study the case of Germany, where the recently emerged right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has developed a major social media presence. We show that right-wing anti-refugee sentiment on Facebook predicts violent crimes against refugees in otherwise similar municipalities with higher social media usage. To further establish causality, we exploit exogenous variation in major internet and Facebook outages, which fully undo the correlation between social media and hate crime. We further find that the effect decreases with distracting news events; increases with user network interactions; and does not hold for posts unrelated to refugees. Our results suggest that social media can act as a propagation mechanism between online hate speech and real-life violent crime.

Keywords: Social Media, Hate Crime, Minorities, Germany, AfD

JEL Classification: D74, J15, Z10, D72, O35, N32, N34

Suggested Citation: Müller, Karsten and Schwarz, Carlo, Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime (May 21, 2018). Available at SSRN:

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3082972 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3082972